During the recent years in Sweden, one of the major issues discussed regarding artists’ conditions has been the MU Agreement, which guarantees payment to the artists for the work done in the framework of exhibitions. This is not just an exhibition fee, but also an hourly pay for all work that the exhibition requires. In this model an artist working for an exhibition is regarded momentarily as yet another paid worker in the art institution. Of course, a totally different question is whether the agreement is being followed according to the rules, or to which art institutions this agreement even applies to. These questions have been interestingly mapped by the Reko collective and are discussed by Erik Krikortz in this publication. In Finland, however, a similar regulation does not exist, and the situation is quite the contrary.

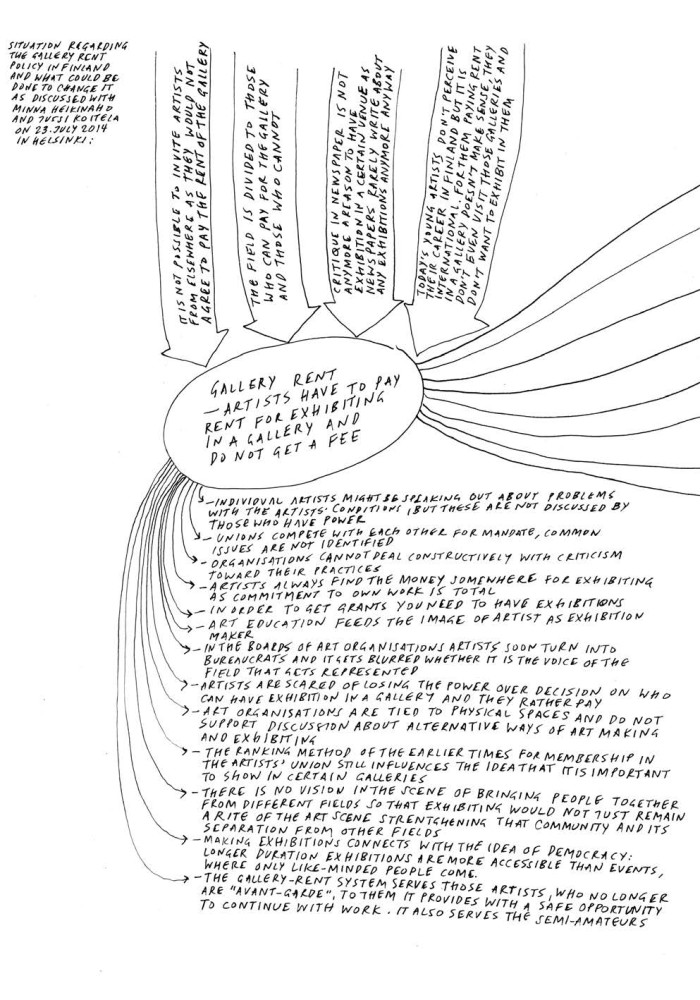

In this contribution I include interviews with active freelance artists in the field, Elina Juopperi, Jussi Kivi, Raakel Kuukka and Marge Monko, as well as a diagram-drawing made on the basis of discussions with artist Minna Heikinaho and artist / freelance curator Jussi Koitela. My aim is to describe the problematics of the situation, whereby making an exhibition can be an enormous economic burden for the artists themselves. I will try to propose ideas how the practice should be changed in order to improve the precarious living and working conditions of artists and art workers. I do acknowledge that in these times of budget cuts of art and culture, any critique toward the structures of art is extremely risky: it can be used as an excuse to transform the existing institutions – which can be seen as remains of social democracy – into neoliberal creative hubs and clusters. In the scenario desired by the advocates of neoliberalism, public funding is reduced to the barest minimum, and strategies of the corporate world are adopted as a necessary precondition for the existence of cultural institutions. Thus, in these risky times, we have to acknowledge the good sides of the present structures, and try to do our fullest to improve them even further. This is my aim in this contribution.

The Way of Finland

Traditionally Finland and Sweden have shared many characteristics of the famous Nordic Social Democratic Welfare structure that has been developed since the World War II. Ever since the mid-1990s, this model has been thrown into question and dismantled bit by bit; in fact, some argue that the paving of the road toward increasing privatisation already started in the 1970s. Nevertheless, the reputation of Finland and Sweden, as well as other Nordic countries, as countries with highly equalising social security still remains. Many people, including many artists, think that this is still the case. In Finland, the freedom of art is declared in the very constitution, which states that sufficient material conditions must be guaranteed for practising art professionals. However, art policy researcher Pauli Rautiainen explained to me in a private conversation that in 2008 private funding for individual artists surpassed the amount of public funding in Finland. 1

After having steadily grown since the World War II, public cultural funding in Finland began its first decrease in 2014. This means that private money, which is usually invested in equities, has become more significant than the public. Whereas private money is gaining more dominance in cultural funding, public money is gradually becoming complementary to that. We can only hope that private funders, who rely on profits from the capitalist system and don’t have any obligation to support independent or experimental forms of art, do not get bored with it or move their support somewhere else. It is also a matter of hope that the private funding would respect some basic principles of “democracy” in terms of distribution mechanisms, not privileging only certain disciplines, contents, institutions, or even ethnicity, gender or age groups of artists who receive funding.

In Finland, the situation regarding artists’ income is, and has been, less prosperous than in the other Nordic countries. According to the research by Tarja Cronberg, artists in Finland have less income than their colleagues and peers in other Nordic countries: the grant system is remarkably weaker, lacking for example long-term grants. 2 In Norway and Denmark, there is an “income guarantee,” which secures a certain level of income to artists who are granted with this guarantee. In Sweden, a similar principle was also practised until the previous centre-right government abolished it, and channelled the funds into multi-year working grants instead. However, in Sweden, there are still some older artists, who have an income guarantee. Proposals for artist salary and income levelling programme were also discussed in Finland during the 1970s, but the Oil Crisis of the 1980s halted the discussion. As a compromise, 15-year grants were introduced in Finland in 1982. However, they didn’t even survive the first grant cycle – during the recession in 1994, the Finnish Parliament decided to put an end to the long-term grants of such duration. The decision was mainly justified with the argument that artists’ work needs to be re-evaluated regularly, while 15 years of steady income is too long period away from control. It was also claimed that long-term grants can result in unproductive activities, or even alcoholism.

Currently, the longest artist grant in Finland is limited to the period of 5 years. A renowned artist can also be granted with an artist pension. This so-called “extra artist pension” is granted by the Ministry of Education and Culture upon the recommendation of Arts Promotion Centre Finland. In 2014, it was given to 59 persons (from all disciplines), whereas the number of applicants was 492. According to a report by Kaija Rensujeff, published by the Arts Promotion Centre Finland, visual artists had the lowest annual average income within the arts sector in 2010: it was 16 000 euros, out of which 8 000 was grant income. 3 When public institutions exhibit the work of an artist in Finland, they pay a copyright fee. The fees are collected by Kuvasto, the Finnish Visual Artists’ Copyright Association, and distributed to the artists in annual instalments. Very often the Kuvasto fee is confused for an artist fee by the museum representatives. However, the Kuvasto fee is clearly a copyright fee for each public use of an image or artwork, but not the remuneration for the work done. Furthermore, it is quite a small fee, and comes very late, so it hardly counts as wage.

Kuvasto rates for exhibition fees in 2014:

Performance 231 € / performance

Installation 116 € / work made in a given room or space, not solid, also land art

Video, CD-ROM 116 € / piece

Sculpture, painting, photograph 58 € / piece

Drawing, graphic print 58 € / piece

Medals 23 € / piece

The fee relates to an exhibition duration of 30 days, calculated according to the time when the exhibition was open for public. When the exhibition time is extended, the rate raises in the following way:

Until 60 days 20 % addition

Until 90 days 50 % addition

Until 120 days 100 % addition

When the same artist has many works in the exhibition, the exhibition fee is determined as follows:

Minimum fee 116 € / artist

Maximum fee 1 575 € / artist

Currently the Artists’ Association of Finland and the Finnish Association of Designers Ornamo are lobbying for an equivalent of the Swedish MU Agreement in Finland. In their announcement, the Artists’ Association of Finland stated that in 2012, 447 exhibitions took place in the 55 art museums of Finland, but Kuvasto fees paid to artists during that year were only 107 306 euros in total. 4 That sums up to the average of 240 euros of Kuvasto fees paid per exhibition, or to calculate it another way, of 1 951 euros of fees paid per museum during the entire year.

The situation of artists in Finland becomes even more peculiar and precarious when the gallery-rent issue is considered. In Finland, it is customary that artists and other freelance art workers are not only working without payment, while contributing to the programme of art institutions, but they even pay for it from their own pocket. Most of the contemporary non-profit art spaces in Helsinki charge rent for exhibiting. Almost all spaces, other than museums or commercial galleries function with this logic. The rent starts from 200 euros in small artist-run spaces, and can reach ten thousands euros in the bigger spaces, such as Kunsthalle Helsinki. For more details about the costs related to exhibiting in the Kunsthalle, see interview with Raakel Kuukka.

Commercial galleries in Finland do not charge rent from artists who are exhibiting. A commercial gallery in this case refers to a space, where an artist is invited to exhibit. It also often entails an ongoing relationship and long-term commitment between the artist and the gallery: the gallery represents the artist, actively aims to sell their work, and takes a certain percentage of all sales, also including the works sold from the artist’s studio. The commercial gallery scene in Helsinki is very small, and the ones that somehow manage to run a profitable business can be counted on one hand. The art market is nearly non-existent and museums don’t have many possibilities to collect. As far as I know, there are no public or private collectors in Finland who would have a substantial impact on the income of artists. However, Frame Visual Art Finland, an organisation that used to fund the participation of Finnish artists in important international art exhibitions, now seems to be thinking that commercialisation is the solution to problems related to artists’ income. After suffering from serious budget cuts during the recent process of restructuring, Frame’s primary interest now appears to be oriented at promoting Finnish galleries in international art fairs.

History Behind the Gallery Rent

The first artist-run gallery in Helsinki was Cheap Thrills, which was run by a group of artists known as Elonkorjaajat (The Harvesters) from 1970 to 1977. The gallery was in the very south of Helsinki in a jugend-style house in Huvilakatu. During its seven years of existence, it hosted some 70 exhibitions. Among the artists exhibiting there were for example Per Kirkeby, Douglas Huebler, H. G. Fagerholm, and Olli Lyytikäinen (his first four exhibitions were in Cheap Thrills and they were each sold out). According to one member of the Harvesters, artist and art critic Jan Olof Mallander, Cheap Thrills already functioned with a sort of artist-pays logic. However, the rent was very low, and the artists could pay it with an artwork if they didn’t have money for rent. Mallander was himself living in the back room of the gallery and paid half of the rent, 200 FIM (approx. 33 euros) out of 400 FIM (approx. 66 euros).

There was a sort of arte povera or fluxus attitude present, as he describes it. Mallander remembers that he once sold London Knees, a multiple piece by Claes Oldenburg that he owned, to the State Art Museum Ateneum in order to cover for the unpaid rent at Cheap Thrills for an entire year. This sort of flexibility in paying rent was possible, in the words of Mallander, largely due to love for art by the “civilised and humane” property owner. 5 As I understand it, having talked with several art workers active in the field in the 1980s and 1990s, the gallery rent policy started as a kind of democratisation of the scene. Artists were fed up with the elitism of the big institutions which would only work with their favourite artists.

For others there were not many opportunities to present their work. In the 1990s, artists in Finland still needed to collect points by making exhibitions in certain approved places and participating in particular annual exhibitions which were considered eligible for the ranking system. A certain amount of points opened the doors to membership in the artists’ associations. It also guaranteed entry in the respected artist directory taiteilijamatrikkeli which functioned as a status indicator. The ranking system with its connected privileges used to be the mechanism of measuring professionalism in art. Needless to say, professionalism is a precondition for getting grants. Thus, artists who were left out of the system, or who just did not want to follow the institutionalised path, founded their own spaces, where they could show their work independently from big institutions. Hannu Rinne writes in Taide (3 / 1995) about the founding of interdisciplinary artists’ association MUU ry in 1987, summing up the purpose for the association: “most important was to create collective spirit and to give home to homeless artists, whose artworks were not necessarily even understood as art. [ … ] The [ MUU ] gallery commenced with a series of changing exhibitions and the idea was to operate as spontaneously as possible, without heavy mechanism of selection committee.” 6

Thus, starting one’s own gallery was also seen as a possibility to act more spontaneously. Initially, the rent was often low in these spaces, but has gradually climbed up hand-in-hand with the gentrification of “artistic” neighbourhoods. Forum Box is one of the oldest artist-run galleries that still exist in Helsinki. It was founded in 1996 as a non-profit space and co-operative for free art of all kinds, with the goal to promote Finnish cultural life. Artist Pekka Niskanen remembers in a Facebook post that during the 1990s, when the Interdisciplinary Artists’ Association MUU ry’s gallery was at Rikhardinkatu, the associated artists didn’t need to pay rent for the space. 7 At that time, also a printed newsletter was produced. Nowadays MUU ry has two exhibition spaces, and in both they charge rent from artists. Also they co-host an art fair together with the Union of Artist Photographers, where artists pay 20 euros participation fee, and the organisers charge 30 % commission of sales.

The exhibition spaces of the artists’ associations as well as the independent artist-run spaces usually cover their rent expenses by charging it from artists who exhibit. Pauli Rautiainen explains the “twisted role” of the gallery rent system from the perspective of artists as a mechanism of building merit rather than selling. 8 When earlier the purpose was to collect points, more recently it has been to invest in one’s career, hoping to find financial compensation for it one day. It is a vicious circle: artists need to exhibit to be able to receive grants, and they need grants in order to exhibit.

There is no doubt that running a gallery space at a prestigious address in the city centre of Helsinki takes a lot of resources, as property prices are high. All artists’ associations have their gallery spaces in the very centre of Helsinki. They all function according to this logic, despite getting public funding. There also appears to be no reflection about the obvious contradiction that some of those associations define their purpose in terms of defending the professional, economic and social interests of their members. I argue that this bad policy introduced by the artists’ associations has been uncritically adopted by many new artist-run spaces which mostly also charge rent from the exhibiting artists.

Some Bad Examples

In Finland there are five artists’ associations: the Association of Finnish Sculptors, the Union of Artist Photographers, the Interdisciplinary Artists’ Association MUU, the Association of Finnish Printmakers and the Finnish Painters’ Union, which are all members in the umbrella organisation the Artists’ Association of Finland. The artists’ associations’ galleries accept exhibition proposals usually twice a year, and the prices are lower for members than for others.

Prices of galleries run by artists’ associations ( December 2014 ):

Gallery Sculptor 3 weeks 3 150 € ( members 2 750 € ) + 35 % provision of sales

Gallery Hippolyte 4 weeks 2 700 € ( members 2 300 € )

Hippolyte Studio 4 weeks 660 €

Gallery MUU, entire gallery ( front space and studio ) 6 weeks 2 280 € ( members 1 995 € )

Gallery MUU, front space 6 weeks 1 915 € ( members 1 680 € )

Gallery MUU, studio 6 weeks 840 € ( members 735 € )

Gallery MUU, Cable Factory 6 weeks 650 € ( members 500 € )

TM-gallery 3 weeks 1 886 € ( members 1 550 € )

The TM-gallery rent is conditional, and the lowest price compared to other galleries listed here is dependent on the state grant toward the rent costs. If funding is not granted, the rent is 2 900 euros for members and 3 236 euros for non-members. The argument that TM-gallery would need to raise the rent price in case their application for the state grant should be denied, can be understood as a strategic pressure that aims to secure the continuation of received support.

The Printmakers’ gallery stresses in their rent conditions that a possible increase in rent prices during the exhibition period will be added to the rent price charged from the artists. Furthermore, in case that the activities of the Association of Finnish Printmakers become VAT eligible, the VAT is added to the rent price. This signals a direct equivalence between the total rent expenses of the gallery and the amount that is charged from artists. It also indicates the attitude of refusing to carry any financial risk, while transferring all uncertainties to individual artists.

It is interesting that when lobbying for the equivalent of the MU Agreement in Finland, the Artists’ Association of Finland and the Finnish Association of Designers Ornamo are not mentioning the gallery-rent issue. One cannot help but wonder whether they see the link between these two issues – how is it possible to introduce an artist fee for exhibitions in a situation where artists are paying rent? Of course, Ornamo and the Artists’ Association of Finland are calling for artist fees in the context of exhibitions in publicly funded institutions only. However, the artists’ associations do receive direct annual (discretionary) funding from the state, and at the same time they charge rent from artists. In these cases, would the artist fee of several hundred euros then be reduced from the rent price of thousands?

It is also questionable whether such scenario wouldn’t just increase the gap between the big institutions, where artists usually do not need to pay rent anyhow, and the small initiatives, where most often artists pay rent. Wouldn’t this gap be reinforced even more, when there is a fee for making exhibitions in big institutions, but the small spaces would still continue to charge rent? It is interesting to note that artist-members of the Finnish Association of Designers Ornamo have recently founded a small 28 m2 gallery space on the “ gallery street, ” the Uudenmaankatu in Helsinki. The O gallery (of artists from Ornamo) was opened in May 2014, around the same time when the discussion about the necessity of the MU Agreement was launched in Finland. It charges 1 100 euros from artists for three weeks (no provision of sales is taken). The use of the gallery space is limited exclusively for the members of Ornamo or other artists’ associations.

Jussi Koitela, artist and freelance curator, wrote about the problem of gallery rent in the Mustekala internet magazine 9, where he noted that the recently opened gallery spaces run by artists’ associations ( such as the above-mentioned MUU ry and the Union of Finnish Art Associations ) are also operating with the same logic of “ artist pays, ” and thus, do not even attempt to change the policy. Koitela also pointed out that the galleries presenting mainly Finnish art in Berlin, Gallery Pleiku and Gallery Suomesta (the name of the gallery contains a cute word play in Finnish language: suomesta can mean both “the swamp place” and “from Finland”), also charge rent from artists. These spaces do not mention the prices on their website. In the online discussion following Koitela’s well-articulated and provocative text in Mustekala, the people running Suomesta clarified that in fact they are not charging rent, but a participation fee. Koitela concludes that although operating outside of the borders of Finland, these two galleries remain part of the extended Finnish art scene rather than the international one – not only because they are clearly focused on presenting art practices from Finland, but also because artists from elsewhere would not agree to pay rent for making an exhibition.

Prices of some independent artist-run and co-operative organised galleries in Helsinki ( December 2014 ):

Myymälä2 gallery 815 € / month ( exhibitions are for 3 or 4 weeks ) 10

Forum Box, whole space 4 weeks 4 200 € 1 / 3 of space 1 550 € , 30 % provision taken for sales ( + 24 % VAT )

Huuto! gallery Uudenmaankatu 3 weeks 1 450 €

Huuto! gallery Jätkäsaari 1 3 weeks 1 350 €

Huuto! galleryJätkäsaari 2 3 weeks 1 350 €

Huuto! Jätkäsaari Kulmio 3 weeks 400 €

On top of the gallery rent, the rental costs of audio-visual display equipment are often not included in the deal with the gallery. Art spaces prefer not to own much equipment, because the digital technology develops very fast and the equipment gets outdated in a speedy manner. Thus, artists are often required to supply the necessary equipment. In addition, some galleries have a rule (or at least a preference) that the equipment must be of the best quality, the latest technology and ultimate professionalism, which is provided by, the one and only, Pro Av Saarikko. Therefore, part of the public grant money for exhibition practice is likely to end up in the pocket of one private business. A few years ago, AVEK (The Promotion Centre for Audiovisual Culture) opened their eyes about this situation and stopped covering the expenses of equipment rent in galleries through their grants. They now try to pressure the galleries into buying their own in-house equipment. Alongside these expenses, there can be the additional costs of printing and posting exhibition cards, or in relation to the opening expenses. In some spaces the artist needs to invigilate the exhibition, at least partly. Some spaces even require a professional translation of the press release in Finnish, Swedish and English. The artist pays!

It is needless to say that when exhibition spaces charge rent from the artists, they do not pay an honorarium to the artists. Thus, the artist needs to find grants not only for all the production and exhibition costs of their artwork, but also for the remuneration of their own working time. In the ideal situation this happens, in reality rarely.

Museums are a safer choice for exhibiting in Finland. Even if they are not always paying artist fees, they at least are not charging rent from exhibiting artists. Museums often follow some kind of artist fee principle, but usually there is no standard fee, as it depends on the overall budget. Sometimes it is only a Kuvasto fee, while on other occasions it is also a proper artist fee. But even if things look nice on paper, it is not always guaranteed that the fee reaches the artist. I can bring a personal example from the Oulu Art Museum, where I participated in a group exhibition in August 2013. For this exhibition, artists were asked to make new works for the public space within the park surrounding the museum. A fee of 1 200 euros was promised in the contract for the new site-specific work, which, from my experience, is quite generous in the Finnish context. Months later, when the work preparations were under way, the curator of the exhibition mentioned passingly in an email that the fee is also supposed to cover all material expenses that exceed the 500 euros that had been budgeted for each work by the museum. This meant that we were expected to use our artist fee to cover the production costs of temporary artworks in an outdoor exhibition which is vulnerable to vandalism and to the rainy weather conditions of autumn months. Most likely there would not be much left of these artworks after the exhibition closes – neither to be exhibited again, nor to be sold.

In recent years, I have also heard of cases when museums announce an open call for exhibition participation, such as the young artists’ biennial. However, because open calls impose that artists offer their work by themselves, museums often reason that they are not obliged to pay the usual artist fees or Kuvasto fees in such cases. There might even be a small submission fee for project proposals, and no production budget offered. At the same time, the museum might charge an entry fee from the audiences viewing the artworks, and profit with it. For more reflections about the experiences of exhibiting in museums, see interviews with Elina Juopperi and Jussi Kivi. The gallery rent model, as it is practised in Finland, is unknown in most of the Nordic and European countries, and I suspect in the rest of the world too. However, it has been well-established also in Estonia. The gallery rent prices in Estonia are more modest, but so are the rental prices in general, as well as the wages and the volume of cultural support. The impact on the art scene has been probably just as severe as in Finland.

However, the situation in Estonia has recently changed quite significantly in regard to this issue. In the beginning of 2014, the Ministry of Culture introduced a new rule which prohibits galleries to take rent from artists, in case they receive (limited) support from the specific funding scheme, the “gallery programme” of the Ministry. This affected primarily the galleries of the Artists’ Association, forcing them to apply for additional rent money directly from the Cultural Endowment. Until then, the task of fund-raising for supplementary rent costs had been delegated to artists. It was eventually agreed between the Ministry of Culture and the Cultural Endowment that the rent money is granted directly to exhibition spaces, instead of circulating it through artists. Thus, the galleries did receive the funding for rent after all, but the administrative work and stress for artists was reduced. Artists still apply for support from the Cultural Endowment for production costs and working grants, but the rent of the gallery space is no longer their direct concern. Perhaps this kind of redirection of the cultural money circulation could also become possible in Finland, if attitudes were changed. In the summer of 2014, I interviewed Estonian artist Marge Monko, currently living in Ghent, about the principles of gallery rent policy in Estonia. See interview with Marge Monko.

Good Examples & Exceptions in Helsinki

Sinne gallery, run and completely supported by Pro Artibus Foundation, an independent organisation affiliated with the Foundation for Swedish Culture in Finland, previously charged a low rent for the exhibition space (up to 600 euros in a large and beautiful, recently renovated space). In recent years, the gallery has become increasingly active also in producing exhibition projects with international artists, while the remaining exhibition slots are distributed with an annual open application call. The practice of charging rent from the artists who are included in the programme through the open application call (mostly local), but not from the invited guest artists (mostly from abroad), became an obvious contradiction. Hence, from the start of 2014, Sinne gallery stopped charging rent from artists, aiming to give a good example to other spaces as well. Now they are hoping to be able to pay a fee to artists instead.

Helsinki City Art Museum has been running Kluuvi gallery in the city centre of Helsinki. Kluuvi has been located in beautiful premises specifically designed for displaying artworks since 1968, but on the decision of the Helsinki City Art Museum Board, the gallery will be moved within the expanded Helsinki City Art Museum in autumn 2015. The website of the Helsinki City Art Museum states that Kluuvi gallery “ focuses on experimental and non-commercial works of Finnish artists, offering opportunities to projects, which would be difficult to realise elsewhere in Helsinki. ” There has been an obvious conflict with their exhibition policy and the fact that they charge rent from these non-commercially operating experimental (usually younger generation) artists, even if the museum has considered the rent price as modest: “ The City of Helsinki sponsors the gallery financially by charging a very low lease and taking no sales commission. ” The rent price in the Kluuvi gallery has been 505 euros for 3 weeks (incl. 24 % VAT). Compared with the total annual revenues of the Helsinki City Art Museum, approximately 600 000 euros, the rent policy in the Kluuvi gallery seems to have been a matter of principle rather than a serious contribution to the budget. Anyhow, now that Kluuvi gallery is moving to the new location within the premises of the museum’s main venue, they will stop charging rent from artists.

To mention a few other good examples, I would like to point out some smaller organisations which are much more precarious than big museums or galleries run by foundations. Artist-run galleries SIC, Oksasenkatu 11 and the Third Space are among those spaces which have a clear position against charging rent from artists and would rather close the gallery than ask artists to pay for it. To elaborate through these examples, SIC gallery has developed an international “high quality” exhibition programme and has become a venue for some of Kiasma’s side-projects. It has also been quite lucky with receiving significant grants from private foundations. Previously they received an annual grant of 35 000 euros in two successive years from the Finnish Cultural Foundation, and for 2015 they have a grant of 50 000 euros from the Kone Foundation. The Kone grant enables them not only to pay rent and realise their programme, but also to hire an executive director for the gallery. Less secure, perhaps, is their location, which is currently in an old storage building near Länsisatama harbour, next door to the construction site of a new hotel.

Similarly to SIC gallery, the artist-run Sorbus gallery, which is also located in an area of the city that is currently transforming, received 34 260 euros support from the Kone Foundation in 2015 for the project titled Opening the Gallery Scene of Helsinki for New and International Artists – Gallery in Vaasankatu That is Free for Artists. Oksasenkatu 11 gallery is an artist-run space located in Töölö neighbourhood which is a bit more remote from the interests of the city developers than SIC and Sorbus. It is in the same location and premises as the legendary Kuumola gallery that also did not charge rent from the artists. In Oksasenkatu 11 the rent is quite low, and when there are no grants to cover the amount, the group of initiators would pay it collectively. A minus point at Oksasenkatu 11, however, is that the artists themselves need to sit in the gallery during the opening hours, although those hours can be freely defined by the artist.

Another collectively organised and funded space is the Third Space at Viisikulma in Punavuori neighbourhood. The small space manages with low means. In the absence of grants, the people involved share the rental costs, including internet and water. Most of the people running the space are students of Aalto University, so they can borrow equipment from the university. The programme of the Third Space is very discursive and more event-focused than in many other spaces. Curator Ahmed Al-Nawas from the Third Space wrote to me in an email: “ We have applied for a fund to pay the rent last year, but nothing. Next year we hope we would get something at least to pay the rent. But let’s see. It seems that in order to get funding as a gallery here, we are forced to become an institution. ” 11

Impact on the Scene

The consequences of the gallery rent policy on the art scene are highly negative, as elaborated below in following points.

First, the artist takes an economic risk when committing to make an exhibition. There is a long process between the first step of submitting an application to the exhibition space and the final stage of realising the exhibition – usually it takes one or two years. During this time, the artist has to fund-raise for all the expenses, including the gallery rent, while at the same time making artworks for the exhibition. This atmosphere is far from encouraging experimentation, because the economic risk and pressure is constantly looming in the background of creative work. In a private conversation with a representative of one of the artists’ association galleries, I was told that 90 % of artists receive an exhibition grant which covers the gallery rent. But how do the remaining 10 % cover the rent costs? And even for those 90 %, is there anything left from the grant to cover the production costs and other expenses in addition to the rent amount?

Secondly, the artist, by accepting the exhibition time that they initially applied for and thus committing to the exhibition, is likely to end up in a situation of complete self-exploitation. The most pressing expense to be covered becomes the gallery rent. In the lack of funding, other costs are avoided by working for free, asking friends to help out, borrowing items, reducing the quality of the materials, and possibly even taking a bank loan.

Thirdly, the relationship between the artist and the gallery staff is regulated by a contract which offers a strict definition of what the gallery provides and what is the responsibility of the artist. In these negotiations and transactions, there is rarely space for discussion about the content of the exhibition. Often it is not seen as appropriate from the side of the gallery to do so, as the space is essentially being bought by the artist ( see interview with Raakel Kuukka ). The gallery staff provides certain services, and the artist takes care of the artwork, including writing the press release and theorising the work. Although many of these spaces are artist-run, the relations have professionalised to such an extent that there is not any curatorial content-related collaboration. It resembles more a relationship between the tenant and the landlord.

Fourth, the gallery rent policy is harmful for the galleries due to the simple fact that it is impossible to have a curated program, an exhibition policy, or a high quality programme, when you cannot invite artists and projects, but you just have to select from those applicants who are ready, willing and able to pay the rent. With this system it is impossible to organise exhibitions of artists from other countries where the artist-pays model is not practised. No-one is so desperate to exhibit in Finland that they would pay for it, when they can do it for free elsewhere.

Fifth, the grant givers have total power over the art scene. They not only decide which artist is getting living and production grants, but they also decide whose exhibition project is worth the support for the gallery rent. If the gallery staff were able to exercise curatorial tasks by actively looking for new interesting productions in the scene, for example by visiting artist studios, and inviting selected artists to the spaces, the grant givers would not have the sole power of determining whose work deserves to be shown. This would undoubtedly make the art scene livelier and bring content-related discussions into it.

Lastly sixth, the atmosphere with the gallery rent system is not encouraging experiments. Rather than that, it pushes artists to make conventional exhibitions. It motivates the production of artworks that artists hope to sell, in order to get the invested money back at the end of the process. This even takes place in a context where the art market is almost non-existent, and where the galleries which charge rent are usually rather passive regarding selling of works from exhibitions. Moreover, the artists’ dependency on grant givers inevitably influences the content of artworks as well. I would argue that it encourages forms of non-political, non-harmful, instrumental, bureaucratic and nationalist art. The gallery rent model is in conflict with the arms-length principle, where the specialists on the field are supposed to decide on the content instead of the funders.

What Could be Done?

One of the biggest headaches for any art organisation in Finland is that there is not enough support given to art spaces as general funding for their core functions. Instead, the cultural support is mostly given as short-term, project-based funding, ear-marked for a specific purpose. The distribution principles of cultural funding often exclude the possibility of investing it in the “walls” ( i.e. the maintenance of the art space itself ), and the funding is often defined by a theme, duration, medium, geographic focus, expected goals, public impact, etc. The public funds should contribute to the general functioning of the organisations, and more precisely, directly to the rent of the spaces, so that the system of gallery rent, which exploits the artists and destroys the art scene, would become defunct. This would leave it up to the organisations themselves to decide what kind of programme they want to realise, instead of trying to respond to the wishes of the funders.

Another option, of course, is to become more inventive in terms of finding exhibition spaces. Artists could abandon the expensive galleries and go for alternative spaces, such as temporarily empty shop fronts, private apartments or artist studios, public spaces, etc. However, there are several arguments against this: even in the galleries, which are in the very centre of the cities, the audiences tend to be small, often dominated by other art practitioners from the scene. Moving away from the centre is likely to make the scarce connection with general audiences even worse. The position of artists in the society is anyway very marginal, and when pushed to the outskirts of the city, it is likely to become even more so. Also, artist’s work can be very solitary, and for many, the galleries are the contact zones with different publics and colleagues.

From a more critical perspective, it should also be acknowledged that artists are often motors of gentrification, taking over new spaces in the cheap areas of the cities. They help to transform areas of the city which were previously undesired. By turning these uncool areas into the “boheme,” artists trigger a domino effect of rising rent prices which first forces the poorer population to move out. Eventually, once the process of gentrification is under way, the artists cannot afford to stay in these areas either.

The gallery-rent issue has been discussed quite a lot locally in Finland, but without much concrete solutions emerging from the debate. One contribution to this discussion was made by a group of students from the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki, as an outcome of a course which I was running together with Irmeli Kokko in spring 2013. In response to the suggestion by the director of the Arts Promotion Centre Finland, the students drafted a proposal to this funding body, recommending to conduct thorough research on the structural problems in the visual arts field and to develop the grant system in accordance with the various organisations operating in the scene. The proposal was very well drafted and expressed strong arguments, many of which are repeated in this text. As far as I and the students know, however, there has not been any response to this proposal whatsoever. Many artists have addressed the issue of gallery rent. One of them was Susana Nevado who declared a “ one-woman protest ” against exhibiting in galleries where the artist needs to pay rent. This was written about, at least, in the Turun Sanomat, a local newspaper in Turku. 12 In discussion with Minna Heikinaho and Jussi Koitela ( see the diagram in the end of this contribution ) one of the conclusions was that young artists do not accept the artist-pays policy any more. The artists from younger generations do not necessarily relate to the galleries in Finland, but they see their work career as international. For them it is rather irrelevant how the rental galleries in Finland function.

I see it as a problem that critical discussions about art policy often take place in the semi-private contexts of social media, such as Facebook. The readership on social media is limited and old discussions disappear under the mass of new information after a while. The discussions are momentary and limited to a small circle, not addressing the ones who would have the power to change things. They do not have any official status or actual weight, operating more in the register of rumour. This is what happened to the discussion that followed the writing by Jussi Koitela in the Mustekala internet magazine, which started as public commenting in the Mustekala website. Furthermore, since the Mustekala website was redesigned, the comments to Jussi Koitela’s writing in the Mustekala website are not visible any more. Elina Juopperi is calling for more “synergy” between artists and institutions on the art scene. She says that “ we should work together with the institutions for common aims, to put pressure on politicians, as we have the same goal and aim. ” 13 She also proposes that “ the state grants should not be given any more to artists for exhibiting ( private foundations do what they like anyway ): not to museum exhibitions and not in ʻgallery / rental spaces. Instead state grants should be given to artists only for production costs and living expenses.” 14

This is what was done in Estonia from the start of 2014, and it seems that it is working out just fine. Nevertheless, it is too early to estimate the influence on the programme of these galleries. It seems that there are (at least) two registers that the art scene is constructed of, and which exist independently from each other. One of them is about doing artwork and getting the work to be shown to others. The other is related to participating in the value production of the institution and prestige. The rent policy in Finland apparently came about in reaction to the second one, out of the need to democratise the field. Should it be a rule (a bit like in the MU Agreement of Sweden or now in Estonia) that organisations which get state funding cannot charge rent from artists? Is there a risk that this would create a hierarchy between different galleries, where the established galleries get their rent money covered, and have artists queuing wanting to show there; while the less respected ones (which could aim to be more grassroots, alternative and interesting) still have to charge rent from the artists, as they do not get enough financial support, and this is reflected in their programme with less artists wanting to pay for showing work there?

It is characteristic of the impact of neoliberalism in arts policy, that funding for some special individuals, the chosen geniuses, or the “crazy innovative ideas” is plentiful, and the rest of the scene lives in poverty. Similarly, there could emerge a hierarchy between the few selected galleries that get the support, and the rest, which do not get it. But one can also ask: isn’t the whole art field constructed of similar hierarchies? The choices would become more visible and then we could perhaps begin to talk about them and about the principles that the funding of art spaces is based on.

In many ways, the current system is spreading “democratic poverty,” where almost everyone faces the same costs equally. It is a paradox that it is the rent cost which is supposedly guaranteeing the democracy, as in fact some have more resources than others. If the decision about the programme selection was given completely to the galleries, and galleries were able to invite artists to exhibit, it would create more heterogeneity within the gallery field. In fact, more artists would get a chance to exhibit, even those who do not have the financial means, and who are not favoured by the grant givers. Also it would enable curated thematic programmes as well as other kind of discursive and thematic long-term programmes to be developed. Now the situation is such that the galleries are dependent on the exhibition proposals that they receive and they can only make selection within the constraints of the received applications. In other words, they have to choose from the pool of artists who are ready to pay, or to take on the task, and the risk, of trying to raise the rent money.

However, as the gallery rent policy change in Estonia proves, and the fact that the gallery rent is unknown to most art scenes, it is not so difficult to change the situation. Perhaps in the end it is a question of whether artists are in fact ready to hand over the power of decision making to the galleries and curators about who can exhibit and who cannot.

Interview with Raakel Kuukka: https://transformativeartproduction.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/interview-with-raakel-kuukka.pdf

Interview with Elina Juopperi: https://transformativeartproduction.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/interview-with-elina-juopperi.pdf

Interview with Marge Monko: https://transformativeartproduction.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/interview-with-marge-monko.pdf

Interview with Jussi Kivi: https://transformativeartproduction.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/interview-with-jussi-kivi.pdf

This text and the interviews were first published in: Minna Henriksson, Erik Krikortz, Airi Triisberg (eds.) Art Workers. Material Conditions and Labour Struggle in Contemporary Art Practice, Berlin/Helsinki/Stockholm/Tallinn, 2015, http://art-workers.org

Illustration: Part of a drawing by Minna Henriksson

Notes:

- Private conversation with Pauli Rautiainen, 30 September 2014, Helsinki. ↩

- Tarja Cronberg, Luova kasvu ja taiteilijan toimeentulo (Helsinki: Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriöntyöryhmämuistioita ja selvityksiä, 2010). [Creative growth and artists’ income, Expert review by Dr Tarja Cronberg, Reports of the Ministry of Education and Culture, Finland, 2010]. ↩

- Kaija Rensujeff, Taiteilijan asema 2010 (Helsinki: Taiteen edistämiskeskus, 2014). ↩

- Announcement published by the Artists’ Association of Finland, “Ruotsin MU-sopimus takaa kuvataiteilijalle korvauksen taiteellisesta työstä,” 7 April 2014. ↩

- Phone conversation with Jan Olof Mallander, 16 June 2014. ↩

- Hannu Rinne, “Lyhyt historia: Ei muuta vaihtoehtoa,” Taide 3/1995 [translation by Minna Henriksson]. ↩

- Pekka Niskanen, Facebook post on Jussi Koitela’s profile, 20 January 2014. ↩

- Pauli Rautiainen, “Suomalainen Taiteilijatuki: Historia, nykyisyys ja tulevaisuus kuvataiteen näkökulmasta,” speech at Oulun taidemuseo, 4 February 2010. ↩

- Jussi Koitela, “Taiteilija maksaa? Kuratoinnin uhka ja muut pelot,” Mustekala, 16 January 2014, http://www.mustekala.info/node/36031 ( accessed 17 February 2015 ). ↩

- The rent in Myymälä2 gallery used to be 300 euros / week for artists. But now that there are increasingly more artist-run spaces not charging rent from artists, they are also forced to rethink their policy. The aim of the Myymälä2 gallery, where rent price is 1 240 euros / month ( which is much higher than in many other artist-run spaces, such as Sorbus with 300 euros / month ), is also to reach a situation with grant support, where artists are not charged the rent. ↩

- Personal email from Ahmed Al-Nawas, 26 November 2014. ↩

- “Kuvataiteilija Susana Nevado haluaa palkan työstään,” Turun Sanomat, 23 May 2014. ↩

- Interview with Elina Juopperi, 6 August 2014. ↩

- Personal email from Elina Juopperi, 12 August 2014. ↩