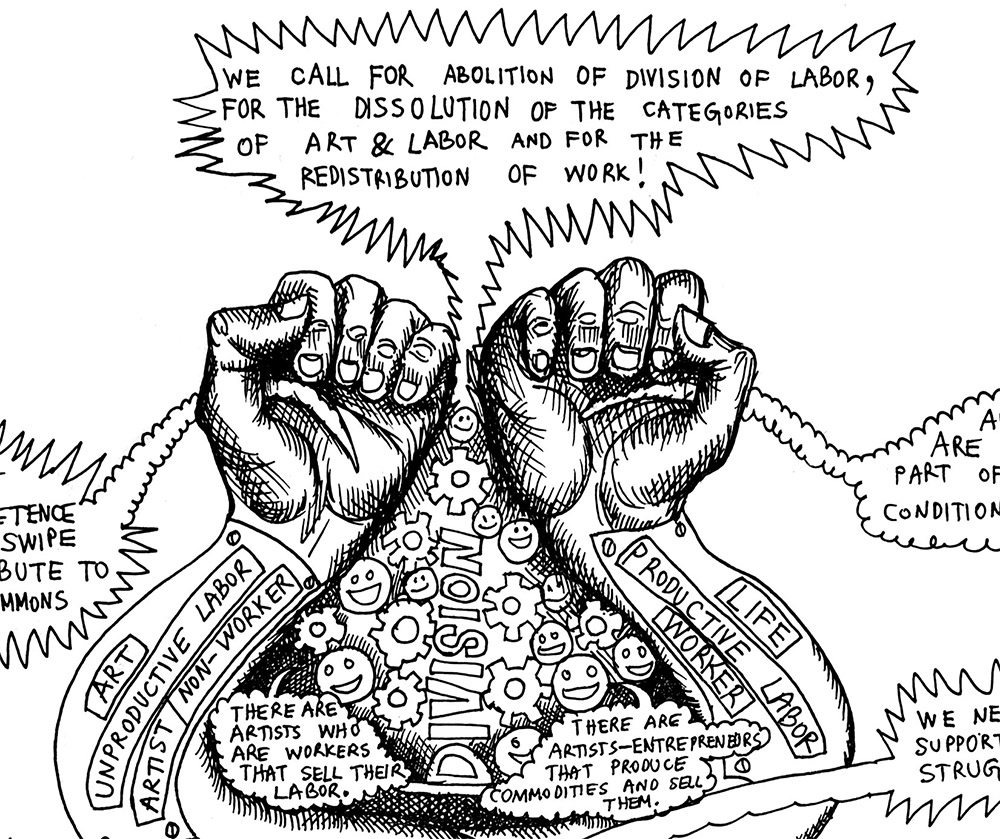

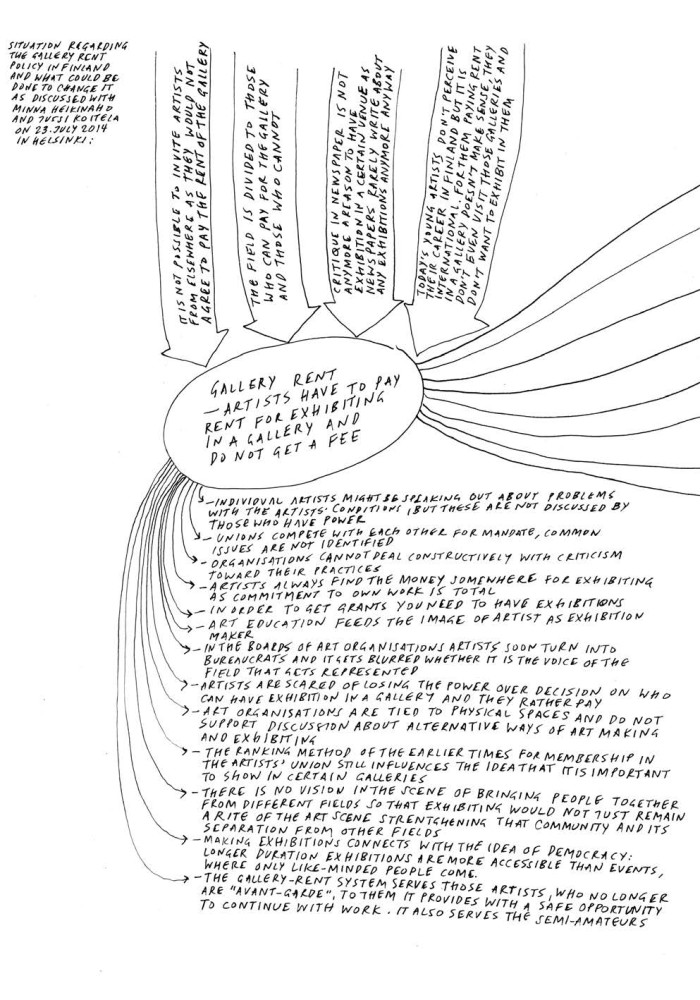

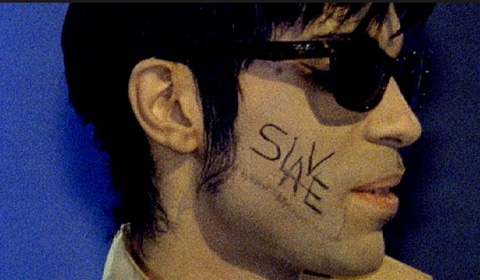

Conclusions of the Trondheim Seminar The Trondheim Seminar This paper presents the conclusions of the Trondheim Seminar on transformative art production and coalition-building, curated in September 2015 by Rena Raedle and Vladan Jeremic as guest curators at LevArt.