On present-day and historical stakes

In the backstage of art fairs, biennales, shows, before artworks are exhibited, sold, collected or gifted, artists, interns, assistants, handlers, curators research and plan, they acquire working materials, necessary tools, to draw, to write, to build, to rehearse, or to film, to publicize and invite audiences on social media. Performances, graphics, installations, films, sculptures, documents or paintings, are all the result of artistic labor and of creativity. Despite this reality, on today’s global art market, artistic labor goes unrecognized while the focus falls solely on the tangible results of this labor. As a result, conditions of artistic labor are summarily dismissed as unimportant, frequently among the upper echelons of the art management, and sometimes even among artists. In some cases, when members of the art community do decide to speak out, they face the danger of being excluded from an exhibition or a project, or blacklisted from working in certain institutions.

This critical state of affairs is not a sine qua non. The widespread belief that artists are far too independent and focused on their own work to self-organize and participate in social movements is easily contradicted by a substantial amount of historical examples when artists came to work together in unions, communes, associations, guilds, syndicates or collectives. Many of these started in the mid-19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. What is also important is that these artists were not just seeking better pay, legal rights, and life securities, but also aligned themselves with workers’ movements that challenged the dominant status quo.

Since the second half of the 19th century, when the terms artist, art worker and activist were used interchangeably in the context of the Artists Union inside the Paris Commune, artists have occupied a precarious and consciously in-between position within the class stratification of society. This lineage of self-reflection and resistance can be traced through international avant-garde movements that followed. Within these groups, which I discuss later in this text, artists and art theorists opposed the notion of “art for art’s sake” and attempted to embrace a working class identity even though they widely disagreed about what exactly this entailed. In this sense, we can conceptualize the historical development of engaged art workers as a dialectical relationship between artists and society, wherein the transformation of one cannot occur independently of the other. As I show through my selection of the following case-study examples, collective actions at the macro-level and the grassroots-level could not exist separated from one another.

The artist as art worker and activist: nineteenth century beginnings

In the second half of the 19th century reactionary appeals to an art for art’s sake clashed with principles of an emerging avant-gardism. During the revolutionary period in France, artist Gustave Courbet penned the famous Realist Manifesto (1855), 1 immediately after Marx’s famous Communist Manifesto (1848). While the extent to which he participated in major historical events has been put into question, Courbert’s bold confidence and passionate belief in the artist’s role in changing society – broadly conceived – towards a liberated and socialist future were strongly shaped by these events. Those were turbulent times of class and political conflicts, from the moment the working class entered the scene as an autonomous political force – which was brutally suppressed by the bourgeoisie – to the French workers’ brief, yet powerful Commune.

In 1871 Courbet called on Parisian artists to “assume control of the museums and art collections which, though the property of the nation, are primarily theirs, from the intellectual as well as the material point of view.” 2 Courbet’s statement responded to the paradigm shift of the economic framework, wherein the transfer of capital accumulated by capitalist organizations created a new class.

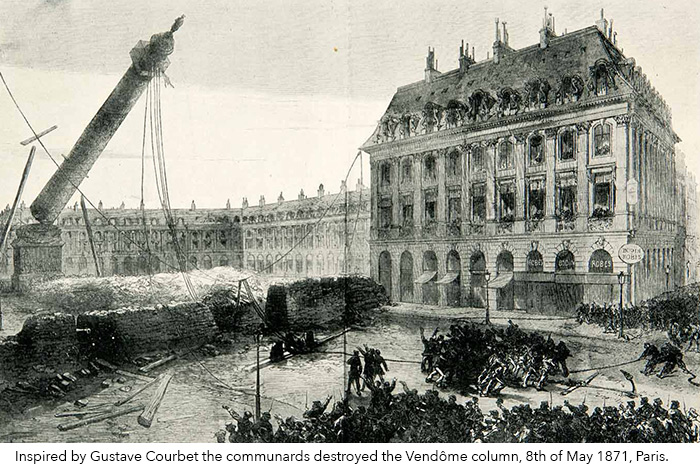

This bourgeoisie had accumulated economic means and invested heavily in the salon art production to flaunt their power. Emerging as new spaces for the presentation and enjoyment of art by the bourgeoisie, the salons of the 19th century operated autonomously from the church and the monarchy; while self-fashioned as disengaged from everyday production, they at the same time built themselves as powerful, independent entities in the field of art. Courbet challenged the salon system and the political classes it upheld through his infamous monumental canvases depicting labor, sex workers and peasants, through his support for the communards’ removal of the imperialistic Vendôme Column in 1871, and his role as commissar of culture in the Commune committee.

The transformation of the artist’s subjectivity as art worker and activist during the latter half of the 19th century, spearheaded by the Realist movement, was an initial landmark moment that continues to define the relationship between art and social movements today. Courbet’s appeal was one of the first instances when artists’ aspiration for social change led them to align themselves with a wider workers’ movement and break with the bourgeois institutions of art and the monarchy. Transgressing from artistic praxis into political action, artists could be considered as a counter-power, occupying political functions in a new order, no matter how briefly this lasted.

Art workers, avant-gardes and new social movements

In the following case studies, I show how artist groups from around the world sought affinities and alliances to various degrees with members of the organized Left, in order to frame the concept of “art worker” as a form of recurring artistic subjectivity under which members of the artistic community mobilized in different context and using different strategies, from artistic interventions to direct actions. Thus my analysis of these groups does not rely on historical causality from one cycle of protest or one movement to another, rather it builds a ground for a comparative study of both continuity and change, overlap and dissonance.

While its participants did not express a specifically socialist position, the DADA movement opposed the values of bourgeois society, political conservatism and the senseless First World War. DADA inaugurated a specific, rebellious attitude towards artistic production, and expressed a set of discontents with the institutionalized nature of the art world. Some members of Berlin DADA sought to identify, at least in theory with the working class, presenting themselves not as artists in service of capital, but rather artists of the working class: art workers. 3 As Helen Molesworth has observed, “Dada’s perpetual return is due to the constant need to articulate the ever changing problems of capitalism and the role of the laborer within it.” 4

Unlike their 19th century predecessors, DADA was mainly a cultural movement spearheaded by artists who had been displaced and disillusioned by WW1, and who used various forms of creative expression to express their anti-war position. Due to this, there was an affinity between the various DADA movements and the Left political parties, especially in Berlin, although, rather than expressing a socialist position, DADA remained heterogeneous and anarchic. DADA’s importance is that the movement sparked an awareness that an artist’s role in society could no longer be considered according to the antiquated and deeply problematic nature of high bourgeois society.

Just a decade later, in Mexico City the groundbreaking Syndicate of Technical Workers, painters and sculptors demonstrated alongside the local proletarian social movement with creative enthusiasm. Even though Mexico had hard won its independence in 1821 from the Spanish Empire, the economic divide between the rich and the poor, and the social gap between the Spanish and Amerindian decedents were glaring, sparking a decade of civil wars in the country.

In their 1922 Manifesto, the Syndicate grasped the general socialist zeitgeist and addressed to “the workers, peasants oppressed by the rich, to the soldiers transformed into hangmen by their chiefs and to the intellectuals who are not servile to the bourgeoisie.” They wrote: “we are with those who seek to overthrow an old and inhuman system, without which you, worker of the soil, produce riches for the overseer and politician, while you starve. We proclaim that this is the moment of social transformation from a decrepit to a new order.” Their goal was “to create a beauty for all, which enlightens and stirs to struggle.” 5

Many members of the Syndicate, which functioned as a guild, joined the Mexican Communist Party (MCP). Their activities were invested both in a new type of collective artistic language, which found its expression in the large-scale educational public murals sponsored by the state, and defending artists rights and interests. 6 However, over the course of the decade, the Syndicate members grew increasingly dissatisfied with the government and began criticizing the post-revolutionary realities in Mexico. The government terminated the muralists’ contracts, expelled them from the Party and the Syndicate gradually dissolved as some of its founders such as Siqueiros emigrated.

In the same timeframe, this time in New York, The Harlem Artists Guild was founded in 1928. Its first president, the artist Aaron Douglas, 7 together with vice-president Augusta Savage and prominent members of the Harlem Renaissance movement (Gwendolyn Bennett, Norman Lewis, Charles Alston and others) agitated for the end of race-based discrimination and for the inclusion and fair pay of African American artists in arts organizations. Although an Artists’ Union existed in New York at the time, these artists felt the necessity for an organization based on the needs of the Harlem artists’ community, that would more effectively represent and lobby for their views and values.

The guild’s constitution stated that, “being aware of the need to act collectively in the solution of the cultural, economic and professional problems that confront us” their goals were first to encourage young talent to “foster understanding between artist and public [through] education” and through “cooperation with agencies and individuals interested in the improvement of conditions among artists,” and finally to raise “standards of living and achievement among artists.” 8 The guild played an influential role in helping artists attain the recognition necessary to qualify them for the WPA (Works Progress Administration) work projects. 9 With the assistance of the Harlem Artist Guild, and the WPA, African American artists succeeded in gaining employment despite the hard times of the 1930s.

Re-adaptations and new cycles of struggle after the second world war

In the post WW2 reactionary period in the United States, The Artists’ Equity Association was established at a time when unions were dismantled, factories purged of women, and the government’s hostility towards artists left them with very little prospects. The Association 10 faced considerable opposition as the idea of organized artists was looked on with suspicion by conservative critics and lawmakers due to a lingering antipathy to the activism of previous groups as the Artists’ Union and the Harlem Artists’ Guild and because of the ideological Cold War mistrust of socialist values.

The Association ended up duplicating some of the activities that concerned its aforementioned predecessors putting in place its own grievance committee. It functioned as a collective working platform, which agitated for improved economic conditions for visual artists, and for the expansion and protection of artists’ rights. Even though it did not endure for more than a decade the Association was a national endeavor, bringing together artist leaders, museum directors and critics to discuss issues around the visibility of the artists and their financial conditions. 11

In the turbulent 1960s and 1970s artists were once more among the first to self-organize, identifying with the workforce under pressure to accept pay cuts, pension cuts and to disband unions. In 1968 France, artists, workers and students, pent up with anger over general poverty, unemployment, the conservative government, and military involvement in Southeast Asia, took to the streets in waves of strikes and demonstrations. Factories and universities were occupied. Atelier Populaire (the Popular Workshop), an arts organization founded by students and faculty on strike at the École des Beaux Arts in the capital, produced street posters and banners for the revolt that would, “Give concrete support to the great movement of the workers on strike who are occupying their factories in defiance of the Gaullist government.”

The visual material was designed and printed anonymously and distributed freely, held up on barricades, carried in demonstrations, and plastered on walls all over France. The Atelier intended this material not be taken as, “the final outcome of an experience, but as an inducement for finding, through contact with the masses, new levels of action, both on the cultural and the political plane.” 12 Unlike its predecessors from the Realist movement, Atelier Populaire did not seek to become a political party or power, but functioned as a critical cultural frame around the social movement in France at the time.

In 1969, in the same turbulent socio-political global climate, an international group of artists and critics formed the Art Workers’ Coalition in New York. Hundreds of art workers participated in the AWC’s open meetings. Its function was similar to that of a trade union, engaging directly with museum boards and administrators who had become the façade of the commercial art world. The group which began around demonstrations at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, presented museums with a list of demands. The group invoked its avant-garde processors in posters, flyers and banners, referring for example to the felling of the Vendôme Column in Paris by the communards in 1878 as an inspiration. They also sought inspiration in the Artists Unions of the 1930s that organized themselves similarly to industrial unions, as well as artist’s guilds in Holland and Denmark, demanding subsidies for universal employment, rather than support from private capital from wealthy patrons. 13

In their famous list of demands, the AWC called for the introduction of a royalties system by which collectors had to pay artists a percentage of their profits from resale, the creation of a trust fund for living artists, and the demand that all museums should be open for free at all times, and that their opening hours should accommodate the working classes. They also demanded that art institutions make exhibition space available for women, minorities and artists with no gallery representing them.

In 1970 the AWC formed an alliance with MoMA’s Staff Association and by working simultaneously from both inside and outside institutional boundaries, their coalition of art-activists and the staff members were able to establish PASTA (The Professional and Administrative Staff Association) in 1970. This was one of the most significant official unions of art workers in the United States, as it joined together the interest of artist with those in similarly precarious conditions who are involved in different aspects of artistic production. 14

Although the Art Workers Coalition folded after three years of intense activities, their legacy of reimagining artistic labor and challenging the unjust and discriminatory institutional models in the United States endured. More recently, with the involvement of the artistic community in social movements such as Occupy, questions of artistic subjectivity and class composition, artists as workers, protest politics and the role or art and artistic institution in the age of the art market have become once again paramount.

Contemporary challenges and new beginnings

Today, it has become clear that artists are pressured to conform to the logic of the art market, even becoming the symbols of the new neoliberal creative economy. As cultural critics such as Gregory Sholette 15 have correctly observed, by coopting the desires and demands of the 1960s and 1970s cultures of protest, businesses and policy makers have transformed the office into more flexible, less hierarchical forms of control, that are increasingly difficult to disentangle and oppose.

At the same time, some artists groups who lead a precarious existence continue to identify as workers, at a time when traditional industries have all but disappeared, when there is no longer the safety net of the extinct welfare states, or as some countries at the periphery of the European Union, where the state has altogether ceased to mediate between the working population and the corporate empire. While the 1% enjoy their prosperity, it is by now abundantly clear that the many have not taken advantage of the trickle-down effect.

In the art world, even blue-chip artists deal with constantly changing occupations, traveling from one art fair to another biennale to another major exhibition, with exhausting networking and publicizing. While even the successful artists struggle, there are also those many artists whose production is invisible, yet completely necessary for the art world to go on spinning. Those young art students, newly graduated from academies and universities, have to deal with not being able to afford a studio, with scrambling for teaching positions, with having almost no health benefits. For the most part these artists end up as manual producers, whose skills such as painting, welding, casting, designing, are employed by the knowledge producers.

This labor hierarchy illustrates the widening divide between the very few artists who are successful and the many that are not privy to the wealth of today’s art world. The latter, like other precarious workers continue to struggle to get to the right side of (art)history, to escape their condition of have-nots. In such difficult times, collective political organizing has become once again necessary. On the backdrop of social movements who are tackling the side-effects of the so-called financial crises around the world, the destruction of educational and cultural structures together with the rise of the right wing and nationalist sentiments, some art workers’ groups also began engaging with the artistic equivalent of the military-industrial-complex.

Currently there exist international self-organized coalitions, collectives, brigades, forums, assemblies, a loosely united, international art workers front working to disentangle the problematics around the tightening mesh of power and capital gripping art and cultural institutions. These groups are tackling issues around precarious conditions, the corporatization of the art world, the privatization of public spaces, self/exploitation, abuse, corruption, and so on, that affect not only the artists in the exhibition spaces, but also those anonymous many who invisibly labor to keep the art world working, those who clean exhibition spaces, guard galleries, those to build art fairs, underpaid or unpaid interns. These initiatives have managed to demonstrate that art workers are not bound to atomized, agent-less subjectivities, and that there is still a genuine desire for significant change in the art world.

In the United States, the New York based group Occupy Museums was born out of the Occupy Movement in 2011, criticizing through direct actions inside museums the connections between the corrupt high finance establishment and a corrupt and tamed high culture. Occupy Museums targeted important private museums in Europe and the United States, and attempt to hold them accountable to the public via means of horizontal spaces for debate and collaboration. Also coming from New York, the group W.A.G.E. is dedicated to drawing attention to economic inequalities that are prevalent in the art world, developing a system of institutional certification that allows art workers to survive within the greater economy.

In London, the group Liberate Tate have engaged in a continuous wave of creative disobedience against Tate Modern, urging them to renounce funding from toxic oil companies. In the same city, the groups Precarious Workers’ Brigade and Ragpickers have come out in solidarity with those struggling to survive in the so-called climate of economic crisis and enforced austerity measures, developing social and political tools to combat precarity in art and society.

In Russia, the May Congress of Creative Workers, established in 2010 in Moscow, have acted as an organizational frame feeling the need to research the motivations, urgencies, approaches and strategies of cultural workers for survival, in the context of the tenuous production conditions in Russia and Ukraine – characterized by different levels of oppression, abuses of authority and even physical violations. Between 2010 and 2013, the Congress functioned as a tool of exercising the power to formulate grievances about particular working conditions and working towards establishing structures and alliances to improve them. More recently in February 2014, during the Maidan Revolution in Ukraine, a group of artists and activists decided to occupy the Ministry of Culture in Kiev and launched the Assembly for Culture in Ukraine, demanding ideological, structural and financial restructuring of this important organizational body.

While not all its members self-identified as art workers, the assembly continues to work in the same building as an ongoing meeting of citizens who are concerned with how cultural processes in Ukraine are structured and intent on transforming these structures and pressing the Ministry of Culture to shift the vector of influence on culture from government ideology to the masses who are the recipients and creators of cultural products and processes.

When ArtLeaks, 16 the organization I co-founded in 2011 was launched, it was in the larger context of social movements and establishment of several of the aforementioned activist initiatives. Unlike many activist groups, which function under an anonymous, collective identity, it was important to us to use our real names and make concrete demands, to take responsibility and not make it leaderless project, which could provoke suspicions. The platform has maintained an international scope, while its goal has been to unite not just artists, but also curators, critics, philosophers around issues, problems and concerns in different contexts and using diverse strategies from “leaking” to self-education, unionizing, and direct actions.

Similar to our online case archive, Bojana Piškur, of the Radical Education Collective 17 in Ljubljana, together with Djordje Balmazović, a member of the Škart Collective, Belgrade, have put together a research investigation, “Cultural Workers’ Inquiry,” 18 based on Marx’s Workers’ Inquiry and concerning the position of a handful of cultural workers in Serbia in 2013. The publication, which is freely accessible online, contains straightforward testimonies of censorship, corruption and discrimination given by the respondents.

Activist groups engaged in similar struggles and activities with ArtLeaks, such as the above-mentioned Precarious Workers’ Brigade, 19 Occupy Museums, 20 Liberate Tate, 21 and the May Congress of Creative Workers, 22 have maintained fluid membership and loose hierarchical structures, making a difference without institutional support or funding. It doesn’t follow that these groups don’t have any resources – if thinking of resources not just as capital, but also as key people, experience, activist know-how, organizational knowledge, etc. They are reacting against the limits of institutions and the need to re-think them, re-write their missions, fight against proliferating repression and tacit abuse – the cultural side-effects of neoliberalism.

These networks do not necessarily imply a consensus over the self-identification of art workers as part of the same class with common grievances and a common agenda, rather they are grounds for alliances between cultural workers and cultural communities across national borders. Through these alliances, art workers can and do support each other during the creative process and their professional endeavors, which oftentimes unfold in highly unsound or in some context, even dangerous circumstances. The art workers models of organization which I have been discussing here are not the only means by which to precipitate socio-political transformation. Rather, its importance in my opinion is that it embodies the idea of a collective, self-organized, politically concerned project that can lead to the transformation of a society. The concept of “Art worker” is a moniker that helps us recognize the possibility of such a transformation in a historically conscious way.

The future of art workers’ movements

One of the biggest challenges these groups face is a yet-to-be-defined overall strategic vision and the precarious ways in which their activities exist, a condition that is also visible in the current fragmentation of socially engaged, politically committed, activist practices. Categories such as activist art, interventionism, social practice, institutional critique, relational aesthetics, etc., are not cohesive in their tactics or demands, neither are they explicitly affiliated with a broader social movement from which to formulate strategies of social transformation. Arguably, this is in itself symptomatic of the effects of neoliberal ideology: heightened individualism, entrepreneurship, privatization, a do-it-yourself attitude. As a counter-example, early 20th century avant-garde movements found a common ground with the organized, revolutionary Left, while the post war, neo-avant-garde was brought together by the oppositional strategies of the New Left.

And yet, some of activist art worker groups are beginning to look back to the late 1960s and early 1970s, and even further to the mid 19th century, as moments of inspiration for the fight for art workers rights, reclaiming cultural institutions, art and/as labor in a global context. Indeed, today’s art workers need more of that do-it-together spirit, a greater common interest and a more developed strategy and plan for transformation. Although the genealogy of engaged art, avant-garde movements and institutional critique has been historicized, it still holds relevance and inspiration for many activists, for whom the museum, the exhibition space, are still battlegrounds for struggle and conflict, which they do not escape from but engage with, challenge, transform into spaces for the common. Undoubtedly, by remembering and relearning from past endeavors, be they successful or not, current generations of art workers, in the broadest sense of the term, can better imagine their own collective evolution and emancipation.

Image: The fall of the Vendôme Column. Inspired by Gustave Courbet the communards pulled down the Vendôme column, 8th of May 1871.

Notes:

- Gustave Courbet, Realism, Preface to the brochure “Exhibition and sale of forty paintings and four drawings by Gustave Courbet,” 1855, republished in T.J. Clarke, Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the Second French Republic, 1848–1851, (Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society), 1973. ↩

- Courbet, Gustave. “Letter to artists of Paris, 7 April 1871”. In Letters of Gustave Courbet, ed. Petra ten-Doessachte. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992. ↩

- See Brigid Doherty, “The Work of Art and the Problem of Politics in Berlin Dada.” October 105, Summer 2003, pg. 73-92 ↩

- Helen Molesworth, “From Dada to Neo-Dada and Back Again.” October 105, Summer 2003, pg. 180. ↩

- David Siqueiros, et al., originally published as a broadside in Mexico City, 1922. Published again in El Machete, no. 7 (Barcelona, June 1924). English translation from Laurence E. Schmeckebier, Modern Mexican Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1939), pg. 31. ↩

- David Alfaro Siqueiros and Xavier Guerrero, some of the founding members of the Syndicate edited a newspaper associated with the organization, El Machete, which included articles by Diego Rivera and others. ↩

- Through his political activism and artwork, Douglas revealed ideas and values exemplified during the Harlem Renaissance, an artistic movement founded on the ideals of racial pride, social power, and the importance of African culture. During the 1930s, African American history and culture was represented and celebrated through the arts. See: Campbell, Mary, David Driskell, David Levering Lewis, and Deborah Willis Ryan. Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America. New York: Abrams, 1897. ↩

- Republished in Patricia Hills, “Harlem’s Artistic Community,” in Painting Harlem Modern: The Art of Jacob Lawrence, (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2010), pg. 26-27 ↩

- “Works Progress Administration.” Surviving the Dust Bowl. 1998. PBS Online. 6 March 2003, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/dustbowl/peopleevents/pandeAMEX10.html. ↩

- Yasuo Kuniyoshi was the founding figure of the Association, which he began to conceptualize in 1946 together with like-minded friends. ↩

- For more information on the Artists’ Equity Association, please see David M. Sokol, “The Founding of Artists Equity Association After World War II,” Archives of American Art, Journal 39 (1999), pg.17-29 ↩

- Quoted in Kristin Ross, “Introduction,” in Kristin Ross, May 68 and Its Afterlives, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), pg. 17 ↩

- See Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam Era,” (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009) ↩

- For a more detailed history of the Art Workers Coalition, see Julia Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era, (Oakland, CA: University of California Press), 2011 ↩

- Gregory Sholette, “Speaking Clown to Power: Can We Resist the HistoricAL Compromise of Neoliberal Art?,” in J. Keri Cronin, Kirsty Robertson, eds., Imagining Resistance: Visual Culture and Activism in Canada (Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press) 2011, pg. 27-48. ↩

- More about ArtLeaks on our website: http://art-leaks.org ↩

- More about the Radical Education Collective on their online archive: http://radical.tmp.si ↩

- Bojana Piškur and Djordje Balmazović, eds., Cultural Workers’ Inquiry, published online, 2013: http://radical.tmp.si/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Workers-Inquiry_English.pdf ↩

- More about PWB on their website: http://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com ↩

- More about Occupy Museums on their website: http://occupymuseums.org ↩

- More about Liberate Tate on their website: http://liberatetate.wordpress.com ↩

- More about the May Congress of Creative Workers (in Russian) on their website: http://may-congress.ru ↩